Yesterday’s ride was a tough one, climbing rough tracks over Dunslair Heights through Glentress Forest, north of the Glentress 7Stanes MTB trails.

I’ve been writing about — and riding in — this forest for the best part of 40 years. Today’s expansive trail centre, cafe, and adjacent hotel are a far cry from the small nondescript building used by Arthur Phillips in the mid-1980s when he and Edinburgh bike shop owner Robin Williamson created — with ten bikes — the Glentress Mountain Bike Centre.

Arthur used to advertise his and his wife’s holiday business, Scottish Border Trails, in Bicycle Times, the Newcastle-based magazine I cut my teeth on while still at university. Writing about the nascant business I stayed at their B&B and first rode the Glentress trails, which had been marked out by Arthur.

He had a Land Rover, supplied as a parting gift from chemicals firm Scottish Agricultural Industries, and he would bushwhack this thing all over the local hills, including the Minch Moor road, of which I’ll say more in a moment. Arthur was searching for the best MTB trails and I remember several trips to these hills over the years, watching in amazement as his business grew, despite this supposed to be his winding down time.

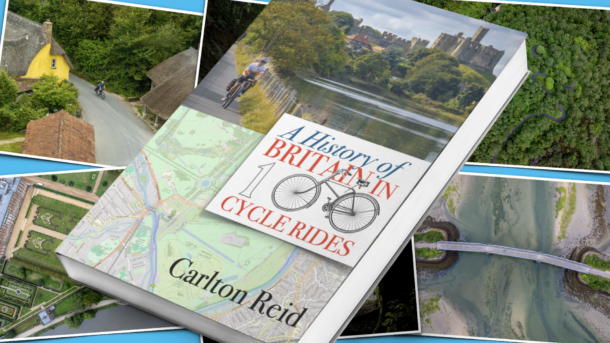

I don’t ever remember riding over Dunslair Heights, and by the state of the trails up there now (overgrown with grass and with many fallen trees blocking the way), I don’t think many come this way. Why bother when there’s a well-maintained MTB trail centre nearby? I bother, and it’s part of a 54-mile loop I curated for my forthcoming book, starting at the trail centre but not using it. The loop does use some of the Innerleithen 7Stanes trails, though.

After the hairy descent of Dunslair Heights (hairy for me, that is, because I had all my heavy bikepacking kit with me) I arrived back on the narrow asphalt lanes knowing I’d done some serious bushwhacking of my own, through some quite remote, little-visited terrain, and when I looked at the faces of the drivers now paying me only the scantest of attention I felt a little like Rutger Hauer’s “replicant” charcter in the 1982 Ridley Scott film Blade Runner.

Hauer, who co-wrote this part of the script, one of the most moving soliloquys in cinematic history, was about to die (or run out of robot life, anyway) and he memorably monologued:

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe… Attack ships on fire off (the) shoulder of Orion… I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain … Time to die.”

Now, Dunslair Heights are not the wormhole-adjacent Tannhäuser Gate, but the name Tannhäuser comes from German folklore about a knight who had to travel through a fairy gate to get to a fairy kingdom.

And there are loads of tales about fairies, evil elves and other “little people” in this part of Scotland.

Back to Minch Moor, where in The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, a collection of Border ballads compiled by (later Sir) Walter Scott, first published in 1802, he writes about a spring at the top of this moor, just off the ancient Minch Moor road, once a key highway through this part of Scotland.

“It is sometimes accounted unlucky to pass such places, without performing some ceremony to avert the displeasure of the elves,” wrote Scott.

“There is, upon the top of Minchmuir … a spring, called the Cheese Well, because, anciently, those who passed that way were wont to throw into it a piece of cheese, as an offering to the Fairies, to whom it was consecrated.”

Fail to make such on offering — today it’s coins, not cheese, and yesterday a single Jelly Baby had been left — and the fairies/elves/little people will do you some harm on the moor.

I failed to leave an offering of any sort, and yet I got off the hill in one piece. Unless it was the fairies/elves/little people who made me shivver last night? Or maybe it was just the unseasonally cold weather?

I’d made a beeline for the Cheese Well on the Minch Moor Road (Scott locates a scene in his tale The Two Drovers on this former drove road) hoping it would make a good bivvying spot. I could have been warm and dry in the forest by stuffing my Thermarest sleeping quilt and inflatable sleeping mat in the Outdoor Research bivvybag but where was the fun in that? Instead I wanted to sleep at the top of the exposed moor, with the tinkling of the Cheese Well lulling me to sleep.

An interpretation board on a stone base looked ideal to lever my Rab tarp from and, to my immense satisfaction, it made a cosy little covering; I only just got it taut before the rain started.

It’s not the quilt’s fault for my cold feet. This lightweight sleeping quilt is only rated down to 7 degrees C (I had been expecting this to be summer trip, not a winter expedition) and it was likely far colder than that on the windswept moor last night. But was I as cold as I thought, kept awake by the bone-chill of it?

I felt as though I never slept, but my Apple watch told me a different story when I looked at it today. According to the tech — fairies or no fairies — I had a solid night’s sleep. The waking up was more sporadic than I imagined and likely to be because of the noise of the fierce wind flapping the taut tarp, not because I was a shivvering wreck.